Next: Bohr Sees a Chance. And Ups the Ante. Part Two

There can never be complete agreement on international control and the administration of atomic energy or on general disarmament until there is a modification of the traditional concept of national sovereignty. For as long as atomic energy and armaments are considered a vital part of national security no nation will give more than lip service to international treaties. Security is indivisible. It can be reached only when necessary guarantees of law and enforcement obtain everywhere, so that military security is no longer the problem of any single state. There is no compromise possible between preparation for war, on the one hand, and preparation of a world society based on law and order on the other. Albert Einstein, Open Letter to the United Nations, October 1947

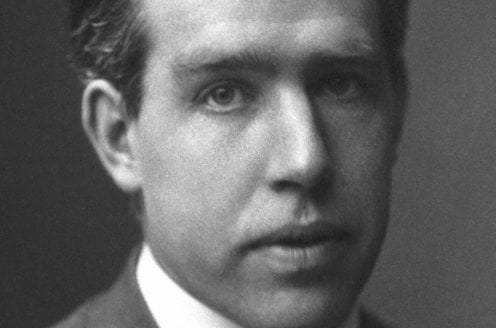

As regards this crucial problem, it appeared to me that the very necessity of a concerted effort to forestall such ominous threats to civilization would offer quite unique opportunities to bridge international divergences. Above all, early consultations between the nations allied in the war about the best ways jointly to obtain future security might contribute decisively to that atmosphere of mutual confidence which would be essential for co-operation on the many other matters of common concern. Niels Bohr, Open Letter to the United Nations, 1950

How hard would it be, in Bohr’s eyes, to realize the “opportunities” that “despite previous disappointments. . . still remain” when it came to achieving international control of atomic energy?

It would be hard, all right. Or at least not easy.

[N]o one confronted with the divergent cultural traditions and social organization of the various countries could fail to be deeply impressed by the difficulties in finding a common approach to many human problems. The growing tension preceding the second world war accentuated these difficulties and created many barriers to free intercourse between nations. Nevertheless, international scientific co-operation continued as a decisive factor in the development which, shortly before the outbreak of the war, raised the prospect of releasing atomic energy on a vast scale.

Bohr does not gloss over “the difficulties in finding a common approach to many human problems” and the “barriers to free intercourse between nations” that had been created by and even “preceding the second world war.” Barriers between the West and the Soviet Union, that is.

He could have mentioned also the barriers that existed within nations. We all knew there were “barriers to free intercourse” in the Soviet Union. Barriers to free intercourse had also been created in this country, however, in 1946 by the McMahon Act. They were also being created, you’d have to say, by hearings that were being conducted in this country these days under the auspices of the House Un-American Affairs Committee.

He saw the “international scientific co-operation” that had existed before the war as an example of how the barriers might be overcome.

Bohr then goes on to quote from the memorandum he wrote for President Roosevelt before their only meeting, in August 1944, “regarding the political consequences which the accomplishment of the [atomic bomb] project might imply.”

Here are some excerpts from that memorandum.

“The fact of immediate preponderance is, however, that a weapon of an unparalleled power is being created which will completely change all future conditions of warfare.”

“Unless, indeed, some agreement about the control of the use of the new active materials can be obtained in due time, any temporary advantage, however great, may be outweighed by a perpetual menace to human security.”

“[T]he further the exploration of the scientific problems concerned is proceeding, the clearer it becomes that no kind of customary measures will suffice for this purpose [that is, to address “the question of control of atomic energy”] and that especially the terrifying prospect of a future competition between nations about a weapon of such formidable character can only be avoided through a universal agreement in true confidence.”

Bohr then quotes from a second memorandum he wrote in March 1945, still before we has successfully tested and used the first atomic bombs. The memo was directed to President Roosevelt and, after Roosevelt died, on April 12, 1945, re-directed to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, though it’s not certain Stimson ever saw it.

In this memorandum, Bohr emphasized the ultimate requirement he saw for control of atomic energy. It was not, in his eyes, as it had been later for Einstein and other scientists, “world government.” A kind of compulsion.

It was instead an “open world.”

Such a world could not be created all at once, he knew that, but it might realistically be arrived at, as Bohr saw it, by smaller exchanges of openness—once the commitment to openness had been made.

The commitment was the starting place.

The ideal of an open world, with common knowledge about social conditions and technical enterprises, including military preparations, in every country, might seem a far remote possibility in the prevailing world situation. Still, not only will such relationship between nations obviously be required for genuine co-operation on progress of civilization, but even a common declaration of adherence to such a course would create a most favourable background for concerted efforts to promote universal security. Moreover, it appeared to me that the countries which had pioneered in the new technical development might, due to their possibilities of offering valuable information, be in a special position to take the initiative by a direct proposal of full mutual openness.

Under the circumstances it would appear that most careful consideration should be given to the consequences which might ensue from an offer, extended at a well-timed occasion, of immediate measures towards openness on a mutual basis. Such measures should in some suitable manner grant access to information, of any kind desired, about conditions and developments in the various countries and would thereby allow the partners to form proper judgment of the actual situation confronting them.

Bohr saw the open exchange of information by scientists, regardless their national origin, that was already happening, when permitted, as an example of what might happen more generally. He also saw “knowledge” as the foundation of civilization.

The very fact that knowledge is in itself the basis for civilization points directly to openness as the way to overcome the present crisis. Whatever judicial and administrative international authorities may eventually have to be created in order to stabilize world affairs, it must be realized that full mutual openness, only, can effectively promote confidence and guarantee common security.

Within any community it is only possible for the citizens to strive together for common welfare on a basis of public knowledge of the general conditions in the country. Likewise, real co-operation between nations on problems of common concern presupposes free access to all information of importance for their relations. Any argument for upholding barriers for information and intercourse, based on concern for national ideals or interests, must be weighed against the beneficial effects of common enlightenment and the relieved tension resulting from openness.

So Bohr recognized that the way would not be easy. There would remain “many problems to ponder and principles for which to strive.” But “free access to information and unhampered opportunity for exchange of ideas must be granted everywhere” in order to “make it possible for nations to benefit from the experience of others and to avoid mutual misunderstanding of intentions.”

An open world where each nation can assert itself solely by the extent to which it can contribute to the common culture and is able to help others with experience and resources must be the goal to be put above everything else. Still, example in such respects can be effective only if isolation is abandoned and free discussion of cultural and social developments permitted across all boundaries.

Bohr looked back on the time of “fervent hope” before the bomb was tested and used.

Looking back on those days, I find it difficult to convey with sufficient vividness the fervent hopes that the progress of science might initiate a new era of harmonious co-operation between nations, and the anxieties lest any opportunity to promote such a development be forfeited.

Of course not everyone had felt those fervent hopes at that time. Not everyone had felt those “anxieties lest any opportunity to promote such a development be forfeited.” What had they felt instead? Overweening pride perhaps? After all we (and our allies, including the Soviets) were about to win a World War that in our case had been fought on two fronts, and were about to invent an atomic bomb. (“Overweening” comes from an Old English word meaning “to be proud, insolent, or contemptuous.” “Overweening pride” has been seen by literary critics as the trait of character that leads to tragedy.)

The letter concludes,

I turn to the United Nations with these considerations in the hope that they may contribute to the search for a realistic approach to the grave and urgent problems confronting humanity. The arguments presented suggest that every initiative from any side towards the removal of obstacles for free mutual information and intercourse would be of the greatest importance in breaking the present deadlock and encouraging others to take steps in the same direction. The efforts of all supporters of international co-operation, individuals as well as nations, will be needed to create in all countries an opinion to voice, with ever increasing clarity and strength, the demand for an open world.

An open world. Can you imagine such a thing? Maybe just barely?

I can certainly imagine becoming committed to it. And then starting to take the small steps toward it Bohr had said would then be possible.

How was Bohr’s letter urging an open world received at the United Nations?

We didn’t have much time to find out. On June 25, 1950, two weeks after the date of Bohr’s open letter, the northern part of Korea, which was run by Communists, invaded the southern part of Korea that had been allocated to non-communists at the end of World War II. The North Koreans were clearly being sponsored by the Soviets even though the Soviets had pulled out of North Korea not long before the invasion. That had seemed encouraging. Had the North Koreans and their Soviet sponsors gotten caught up in a feeling of overweening pride? After all, the Soviets also had won World War II and, as of ten months ago, also had an atomic bomb.

Not to mention the fact that in this year, 1950, Communists in China had won a civil war.

After 1950, Soviets had quickly signed a mutual defense pact with the Chinese Communists.

The UN was asked by the United States and others to approve a “police action” to push back the North Koreans. It was agreed to.

A new war was now joined.

In the late 40’s, one of our best nuclear weapons designers at Los Alamos was a physicist named Ted Taylor. He’d helped “miniaturize” our nuclear weapons. Taylor said, years later, that he and some other weapons designers had justified to themselves their work on nuclear weapons with the thought that nuclear weapons were going to prevent future wars.

The Korean war showed that that isn’t what had happened.

Next: Going for the Super