Bohr Sees a Chance. And Ups the Ante.

A talent for speaking differently, rather than arguing well, is the chief instrument of cultural change. Richard Rorty

[Bohr] was clear that one could not have an effective control of atomic energy, which would permit useful application, and a free science and a free spirit of enquiry, without a very open world. He made this quite absolute. He thought that one would have to have privacy. He needed privacy, as we all do; we have to make mistakes and correct them as we learn better. But in principle everything that might be a threat to the security of the world would have to be open to the world. Robert Oppenheimer, “Niels Bohr and Atomic Weapons,” New York Review of Books, December 17, 1964

Four months after President Truman’s announcement in January 1950 that the United States would be going all out to develop a Super bomb, an Open Letter dated June 9, 1950 was delivered to the the General Assembly of United Nations. The letter had been written by Niels Bohr.

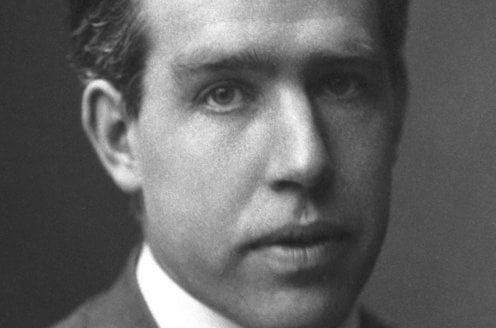

Bohr was the Danish physicist in the Manhattan Project who—even before the first atomic bomb was successfully tested—had tried to get the United States and Great Britain to approach the Soviets about cooperating in the international control of atomic energy. President Roosevelt had seemed to like the idea. Winston Churchill had adamantly rejected it.

After the atomic bombs had been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, Bohr had pretty much withdrawn from the debates and discussions that followed, debates about how to deal with the threat to “common security” that had been created by the invention of nuclear weapons. Immediately after the bombs fell on Japan, he’d written a column that was published in the London Times. Later he’d written some pieces for the publications of the Federation of Atomic Scientists. But after that, he’d stayed out of it, pretty much.

As he said now in the Open Letter,

While possibilities still existed of immediate results of the negotiations within the United Nations on an arrangement of the use of atomic energy guaranteeing common security, I have been reluctant in taking part in the public debate on this question. In the present critical situation, however, I have felt that an account of my views and experiences may perhaps contribute to renewed discussion about these matters so deeply influencing international relationship.

“[T]he present critical situation” he refers to here had to be prospect of developing the Super bomb that President Truman had, five months go, announced the United States would be committed to.

Today, the Super is usually referred to as the “hydrogen bomb.” President Truman had used that expression in his announcement. It has also been called the “fusion bomb” or “the thermonuclear bomb,” with the last of these being the term most often used now. All those labels mischaracterize in some way how the bomb works but we can let that go for now. Nobody calls it the Super anymore.

Let’s look more carefully at what Bohr said in the Open Letter to the United Nations. (Note: Bohr’s writing has sometimes been criticized as “difficult.” I think that’s wrong. If it’s not “plain,” that’s not because Bohr is a lazy writer or unclear in his thinking. Bohr once said that if a choice had to be made, he would rather do justice to his subject than be clear, or, we might say, specious. His writing is not meant to be quick and easy, that’s true, but if we just slow down a little and remember what we are talking about, we should be fine.)

Here’s how the letter to the General Assembly of the United Nations began.

I address myself to the organization, founded for the purpose to further co-operation between nations on all problems of common concern, with some considerations regarding the adjustment of international relations required by modern development of science and technology. At the same time as this development holds out such great promises for the improvement of human welfare it has, in placing formidable means of destruction in the hands of man, presented our whole civilization with a most serious challenge.

The “modern development of science and technology” Bohr refers to here is the release of atomic energy. Bohr’s proposal here is like the proposals he made before the first successful test of an atomic weapon to the scientists at Los Alamos including J. Robert Oppenheimer, then to President Roosevelt, and then to Winston Churchill, who had vetoed it.

The proposal was founded, it seems clear, on a profound principle called “complementarity” that Bohr had intuited in 1927 as quantum physics was being born.

The principle of complementarity recognized that apparently opposed or contradictory or paradoxical ideas may both need to be recognized as valid. That when confronted by an apparent contradiction or paradox, we should not necessarily seek for a single definitive truth that reconciles things.

Bohr had first recognized the principle in 1927 as he pondered the experiments that showed that light acted like a particle sometimes (it really was a particle at those times) and sometimes (really) like a wave—though never both at the same time. Both accounts, though incompatible with each other, were necessary to an understanding of “light,” the principle said, and together they gave a complete account of the matter. No larger principle was to be discovered that would somehow reconcile the two.

In the Open Letter, he was proposing to the United Nations that the release of atomic energy offered “great promises for the improvement of human welfare” at the same time that it presented “our whole civilization with a most serious challenge.”

The aim of the present account and considerations is to point to the unique opportunities for furthering understanding and co-operation between nations which have been created by the revolution of human resources brought about by the advance of science, and to stress that despite previous disappointments these opportunities still remain and that all hopes and all efforts must be centered on their realization.

The “previous disappointments” were those that had followed his first proposals. Looking back at the time of the Manhattan Project’s work to create the first atomic bomb, he remembered,

Everyone associated with the atomic energy project was, of course, conscious of the serious problems which would confront humanity once the enterprise was accomplished. Quite apart from the role atomic weapons might come to play in the war, it was clear that permanent grave dangers to world security would ensue unless measures to prevent abuse of the new formidable means of destruction could be universally agreed upon and carried out.

Again, Bohr finds a complementary aspect to the current gravely dangerous circumstance. The “danger” presents “opportunities.”

As regards this crucial problem, it appeared to me that the very necessity of a concerted effort to forestall such ominous threats to civilization would offer quite unique opportunities to bridge international divergences. Above all, early consultations between the nations allied in the war about the best ways jointly to obtain future security might contribute decisively to that atmosphere of mutual confidence which would be essential for co-operation on the many other matters of common concern.

Those “early consultations between nations allied in the war”—the United States (and its allies) and the Soviet Union—had never taken place. Winston Churchill had seen to that. Joseph Stalin, the dictator of the Soviet Union, might also have torpedoed any such discussions, or he might not have.

He didn’t get the chance to show which.

Bohr was saying he might now be given that chance.

Next: Niels Bohr Sees a Chance. And Ups the Ante. Part Two